Table Of Content

“Time,” on the other hand, has a different ontological status from the substantive variables in the longitudinal study. There are at least three ways to describe how time is not a substantive variable similar to other focal variables in the longitudinal study. First, when a substantive construct is tracked in a longitudinal study for changes over time, time is not a substantive measure of a study construct. In the above example of newcomer adaptation study by Chan and Schmitt, it is not meaningful to speak of assessing the construct validity of time, at least not in the same way we can speak of assessing the construct validity of job performance or social integration measures. Second, in a longitudinal study, a time point in the observation period represents one temporal instance of measurement. The time point per se, therefore, is simply the temporal marker of the state of the substantive variable at the point of measurement.

How long is a longitudinal study?

Another possible reason for changing measures is poor psychometric properties of scales used in earlier data collection. Previously, researchers have used transformed scores (e.g., scores standardized within each measurement point) before modeling growth curves over time. In response to critiques of these scaling methods, new procedures have been developed to model longitudinal data using changed measurement (e.g., rescoring methods, over-time prediction, and structural equation modeling with convergent factor patterns). Recently, McArdle and colleagues (2009) proposed a joint model approach that estimated an item response theory (IRT) model and latent curve model simultaneously. They provided a demonstration of how to effectively handle changing measurement in longitudinal studies by using this new proposed approach. Another form of discontinuous change is one in which the discontinuous event occurs at varying times for the units of observation (indeed it may not occur at all for some) and the intervals for collecting data may not be evenly spaced.

Smart Surveys

Association between baseline levels of muscular strength and risk of stroke in later life: The Cooper Center ... - ScienceDirect.com

Association between baseline levels of muscular strength and risk of stroke in later life: The Cooper Center ....

Posted: Fri, 13 Oct 2023 07:00:00 GMT [source]

Thus, researchers should be aware of the memory-related implications when they choose the time frame for their measures. As with many questions in this article, an in-depth answer to this particular question is not possible in the available space. Hence, only a general treatment of different coding schemes of the slope or change variable is provided. Excellent detailed treatments of this topic may be found in Bollen and Curran (2006, particularly chapters 3 & 4), and in Singer and Willett (2003, particularly chapter 6).

Using data from other sources

For example, psychologists have demonstrated that even over a single episode, people tend not to base subjective summaries of the episode on its typical or average features. Instead, we focus on particular notable moments during the experience, such as its peak or its end state, and pay little attention to some aspects of the experience, such as its duration (Fredrickson, 2000; Redelmeier & Kahneman, 1996). The result is that a mental summary of a given episode is unlikely to reflect actual averages of the experiences and events that make up the episode. Furthermore, when considering reports that span multiple episodes (e.g., over the last month or the interval between two measurements in a longitudinal panel study), summaries become even more complex. For example, recent evidence suggests that people naturally organize ongoing streams of experience into more coherent episodes largely on the basis of goal relevance (Beal, Weiss, Barros, & MacDermid, 2005; Beal & Weiss, 2013; Zacks, Speer, Swallow, Braver, & Reynolds, 2007). Thus, how we interpret and parse what is going on around us connects strongly to our goals at the time.

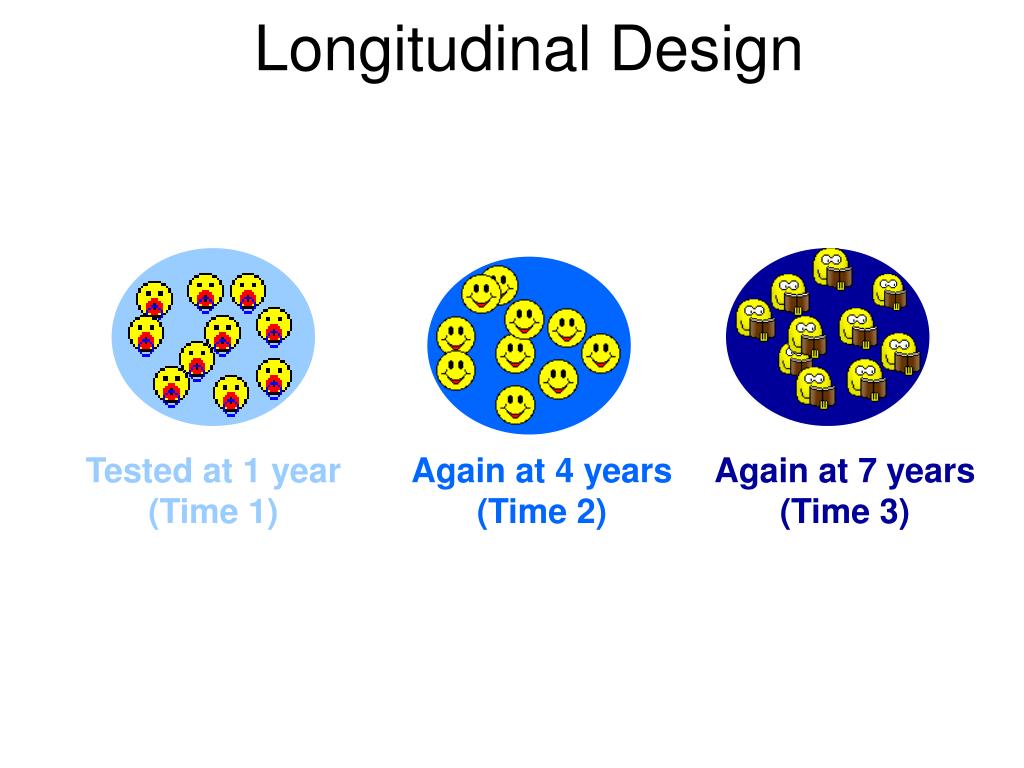

Participants tend to drop out

The correct length of the time interval between adjacent time points in a longitudinal study is critical because it directly affects the observed functional form of the change trajectory and in turn the inference we make about the true pattern of change over time (Chan, 1998). What then should be the correct length of the time interval between adjacent time points in a longitudinal study? Put simply, the correct or optimal length of the time interval will depend on the specific substantive change phenomenon of interest.

Offline Survey

Conceptually, the first slope variable brings the trajectory of change up to the transition point (i.e., the last measurement before the announcement) while the second one captures the change after the transition (Bollen & Curran, 2006). Regardless of whether the variables are latent or observed only, if this is modeled using software such as Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), the difference between the means of the slope variables may be statistically tested to evaluate whether the post-announcement slope is indeed greater than the pre-announcement slope. One may also predict that the announcement would cause an immediate sudden elevation in the performance metric as well. This can be examined by including a dummy variable which is zero at all time points prior to the announcement and one at all time points after the announcement (Singer & Willett, 2003, pp. 194–195). If the coefficient for this dummy variable is statistically significant and positive, then it indicates that there was a sudden increase (upward elevation) in value post-transition. Longitudinal study designs are implemented when one or more responses are measured repeatedly on the same individual or experimental unit.

A number of hypothesis were generated and described by Dawber et al. (10) in 1980 listing various presupposed risk factors such as increasing age, increased weight, tobacco smoking, elevated blood pressure, elevated blood cholesterol and decreased physical activity. It is largely quoted as a successful longitudinal study owing to the fact that a large proportion of the exposures chosen for analysis were indeed found to correlate closely with the development of cardiovascular disease. Numerous variables are to be considered, and adequately controlled, when embarking on such a project.

The 1970 British Cohort Study, which has collected data on the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in 1970, is one well-known example of a longitudinal study. Many governments or research centres carry out longitudinal studies and make the data freely available to the general public. For example, anyone can access data from the 1970 British Cohort Study, which has followed the lives of 17,000 Brits since their births in a single week in 1970, through the UK Data Service website.

How to Perform a Longitudinal Study

This issue has received a great deal of attention in the multilevel literature (e.g., Bliese & Ployhart, 2002; Singer & Willett, 2003), so I will not belabor the point. However, there is one more nonindependence issue that has not received much attention. Specifically, the issue can be seen when a variable is a lagged predictor of itself (Vancouver, Gullekson, & Bliese, 2007). With just three repeated measures or observations, the correlation of the variable on itself will average −.33 across three time points, even if the observations are randomly generated. This is because there is a one-third chance the repeated observations are changing monotonically over the three time points, which results in a correlation of 1, and a two-thirds chance they are not changing monotonically, which results in a correlation of −1, which averages to −.33.

These include factors related the population being studied, and their environment; wherein stability in terms of geographical mobility and distribution, coupled with an ability to continue follow-up remotely in case of displacement, are key. It is furthermore essential to appropriately weigh the various measures, and classify these accordingly so as to facilitate the allocation effort at the data collection stage, and also guide the use of possibly limited funds (3). Additionally, the engagement and commitment of organisations contributing to the project is essential; and should be maintained and facilitated by means of regular training, communication and inclusion as possible. As with other types of psychology research, researchers must take into account some common challenges when considering, designing, and performing a longitudinal study.

Following adequate design, the launch and implementation of longitudinal research projects may itself require a significant amount of time; particularly if being conducted at multiple remote sites. Time invested in this initial period will improve the accuracy of data eventually received, and contribute to the validity of the results. Regular monitoring of outcome measures, and focused review of any areas of concern is essential (3).